|

| Above: Map of Adelaide area with the Hindmarsh and Cox's Creek location marked |

1821 Info 1f for Caleb Crompton |

Caleb’s life and troubles, his homes, his occupations, in South Australia are told through

newspaper article extracted from Trove

(Accessed 12 June 2019).

There are no South Australian Trove references to Caleb between 01 January 1849 and 25 August 1849.

Caleb's movements

Unclaimed letters dated 25 August 1849 suggest Caleb was living in Adelaide or at least was having mail addressed to the Adelaide post office. A notification in The South Australian Register of 10 December 1849 declares Caleb as an insolvent already living in Cox’s Creek as a general dealer. At the time of the 1850 insolvency, Caleb was a general dealer ‘formerly of Hindmarsh’ late of Cox’s Creek. On other occasions, he was recorded as formerly of Cox’s Creek and late of Hindmarsh. This confusing recording suggest he had left Cox’s Creek before 15 February 1850. However, on 11 June 1850 his application for a slaughter licence was made from Cox’s Creek after his Cox's Creek insolvency.

|

| Above: Map of Adelaide area with the Hindmarsh and Cox's Creek location marked |

Caleb sailing from Launceston

Caleb accompanied shipments of corn and horses from Launceston to Adelaide. However, the passenger records give no indication whether Caleb was living in Adelaide or Launceston. His family do not seem to be listed.

Unclaimed letters

25 August 1849 page 1 of the Adelaide Observer makes the first mention of Caleb in the Adelaide press with reference to unclaimed letters at The General Post Office, Adelaide. This suggest he emigrated to South Australia at some time before this date. However, Caleb had been trading hay/ corn and horses from VDL. The last notification for unclaimed letters in Caleb’s name was for 16 April 1850.

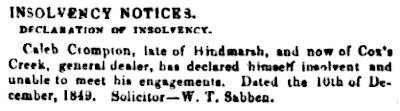

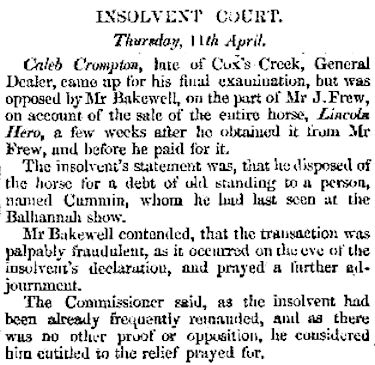

Insolvency

Caleb’s insolvency is frequently reported in the South Australian, South Australian Register and the Adelaide Observer between 10 December 1849 and 22 March 1850. The plaintiff was James Carns [Cairns – see petition of 22 February 1855, in The Argus [1821info1g] in which it is stated on 08 December 1854, shortly before his death, the Newmarket Hotel, already described as a wooden building, placed on two roods of land (½ acre), is being sold at auction for the benefit of James Cairns of Lonsdale Street, Melbourne.

|

| 10 December 1849 - The South Australian Register notification declares Caleb as an insolvent who is living in Cox’s Creek as a general dealer. Caleb declared himself insolvent. James Carns was the suitor – a petitioner or plaintiff. A James Frew is also mentioned. |  |

| 24 January 1850 - Caleb was committed to prison.

Left: Adelaide Goal: a sketch by EC Frome circa 1843 |

|

Hindmarsh

Rear-Admiral Sir John Hindmarsh KH RN (baptised 22 May 1785 – 29 July 1860), after whom the original village was named, was a naval officer and the first Governor of South Australia, from 28 December 1836 to 16 July 1838. The Adelaide suburb of Hindmarsh was originally laid out as a speculative subdivision, the Village of Hindmarsh, on land owned by him. It was for many years the centre of a Local Government Area called the Town of Hindmarsh, which has now been amalgamated into the City of Charles Sturt.

|

| The Adelaide press of 1850 makes frequent announcements of Caleb's pending

insolvency auction. These frequently confirm his properties in Cox's Creek and

section 103 Jane Street Hindmarsh. When Caleb settled there before August 1849

Hindmarsh appears to have been an autonomous established settlement to the west of

Adelaide, bounded by Port Road and the River Torrens.

Section 103 on Jane Street, now stands on the corner of the modern Susan Street and South Road. Right: Adelaide Times 17 July 1850 This information below is taken from part one of the Hindmarsh Heritage Survey Part One: General Report entitled 1838-1852: the first suburban village. As there are no details of Caleb’s life in Hindmarsh, apart from his insolvency, this is written to give a flavour of what Caleb may have experienced in the late 1840s. He is not thought to be an original settler of Hindmarsh. |

|

In 1839, John Stephens, in The Land of Promise, described

“South Australia is, at present, in the ascendant to what is to us a most interesting class of emigrants - respectable labourers and artisans, and intelligent and educated small capitalists, aspiring to improve their conditions or to keep their places in society, after the struggle has become hopeless in the Old World".

Caleb, having crossed the water from Van Diemen’s Land, was not a direct emigrant from the Old World and may not have been the respectable citizen anticipated. It is known that he had had dealings in Adelaide but quite why he chose to take Fanny and his family to Hindmarsh is not, at this moment, known. However, it is known that he possessed section 103 in Jane Street, Hindmarsh sometime in the late 1840s.

At that time, Hindmarsh was a ‘village’ whose development was closely associated with the growth of Adelaide. ‘They are sisters, interdependent and yet distinctly individual. The very physical characteristics of Hindmarsh - and consequently, much of its history and heritage - were determined by the siting of Adelaide.’ Hindmarsh history.

Both Adelaide and the village of Hindmarsh were constructed on the level flood plain of the River Torrens’ fertile alluvial soil with extensive deposits of gravel, sand, clay and limestone. These natural resources fostered the rapid development of industry and agriculture. The river’s waters, forming the southern boundary of the village, provided both water for commerce and drainage for the many drainage gullies that cross the flat area.

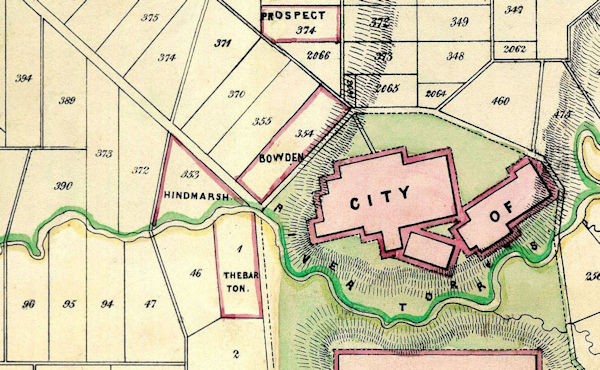

Colonel Light, Governor Hindmarsh’s surveyor, began laying out Adelaide and adjoining country sections of either 134 or 80 acres parcels in 1837. The present Hindmarsh district includes the original preliminary sections numbered 353, 354, 355, 370, 371, 372, 374, 2066 and 2067. Caleb’s half acre, being part of the original section 353, was considered to be in a most favourable located country section.

|

| Above: An 1849 map locating the Hindmarsh district

relative to the city

Source: MapCo Adelaide 1849 (Accessed: 01 August 2019) |

The Governor John Hindmarsh, selected Section 353 early in 1838, for a total of about 73 pounds ($130 in 2019) only. Within weeks he had the triangular section subdivided as “Hindmarsh Town [and sold it] to a number of ordinary people who quite openly stated that they intended to work their own small half-acre lots and form a village."

"When Section 353, Hindmarsh Village, was settled it was called an 'excrescence' [an abnormal growth] ... and a blot on the theory upon which, the infant colony had been so recently founded ... The critics argued that … [the] concept of concentrated settlement meant only one city and the establishment of a secondary town disfigured his theory of colonisation. It struck at the very idea of a colony where the gentlemen were expected to own the land and the free passage labourers to labour for them ... Thus at the outset the working men of Hindmarsh village were not playing the rules of the game. They were establishing themselves as independent of their betters, an independent outpost in & society of higher and lower orders transplanted from Britain." Wimshurst, Kerry, Nineteenth Century Hindmarsh, B.A. Honours thesis, University of Adelaide, 1971, pp 5-6.

Hindmarsh was, therefore, distinctive from the start, firstly as South Australia's first secondary town, and the model for other ‘villages’ around Adelaide. Secondly, Hindmarsh from the start was intended as a self-made and independent working class town governed by an eight member "committee of management", for 200 of the original skilled workers and the lower middle class who had negotiated the sale with the Governor.

The layout of the original village can still be seen in the layout of the roads. It was bounded by John Street (South Road), the River Torrens and Port Road. Port Road eventually became the public and commercial face of the town, while Adam and River streets attracted the tanneries, wool- washing, flour mill and breweries which used the river. The village focus, Lindsay Circus, was set out at the centre of the triangle, part of which was to be a cemetery, but after public opposition it became a reserve. It is now the Hindmarsh Stadium and Oval. A site in the south-west corner of the triangle, which was originally intended as the local market, became the Hindmarsh Cemetery in 1846.

|

| Above: Section map in the Hindmarsh District of area 353

above in 1846. Caleb's section and Jane Street are coloured turquoise. Click on the map to open an A4 pdf in a new window |

The width of the street and the size of the original 200 half-acre allotments provided opportunities for purchasers to build dwellings and to develop diverse cottage or backyard industries and commercial activities. Perhaps, Caleb as a general dealer could have worked from ‘home’.

Hindmarsh developed rapidly. By 1841 there were about 200 houses in Hindmarsh proper, with a population of 661 and with Adelaide's population at 9,000. The new population were engaged in labouring, lime-burning and brick-making and the carrying trade between the port and the city. Others took up backyard tanning, milling and building. Most also took advantage of their blocks by keeping stock and growing food. Several small farms were, established fronting Robert, Torrens and Manton Streets and Torrens and Port Road. Large numbers of pigs and goats roamed the streets and vines and fruit trees grew in the yards, all of which supplemented the working men's daily wages. Shops and hotels were erected, wells were sunk, school classes were conducted and subscriptions were gathered to build a chapel.

The first was to be a "Mud Chapel" built as early as 1838 and then ten years later came a large permanent Congregational Church, which is still standing in Hindmarsh. A non-denominational Christian Chapel was built in 1845, which stands on part of Lindsay Circus, near the corner of Hindmarsh Place and Manton Street, behind the Museum.

In early 1839, with the high demand for Hindmarsh properties, section 354 became the new village of Bowden between Hindmarsh and Adelaide, to be followed by Brompton village in 1849. By the early 1850s, Hindmarsh was described as "thickly inhabited", by the families of farmers, skilled workers and service workers, rising small capitalists and by the labouring poor. The area became a refuge for the very poor if not for some of the criminals of Adelaide. On the other hand, many of the residents were honestly working class in origin aspiring to middle class respectability.

|

| Above: Hindmarsh 1846 with modern road overlay Click on the map to open an A4 pdf in a new window Source: Base map hand drawn from Hindmarsh Heritage Survey Part One (q.v.) |

Despite these emerging class differences, which were physically expressed in the types of housing and the areas within the district in which different groups were located, the locals continued to describe themselves as working class with a strong sense of local identity.

By 1853, families were leaving Hindmarsh to find their fortunes in the gold fields.

|

| Above: A 2019 aerial of Hindmarsh showing the light industries and Caleb's section in turquoise |

|

| Above: Caleb's section in 2019, now TrailerCo of 59 South Road, Hindmarsh, 5007, with access off Jane/Susan Street |

Additional research by Heather Schoffelen - with thanks

Newspaper records of Caleb's insolvency

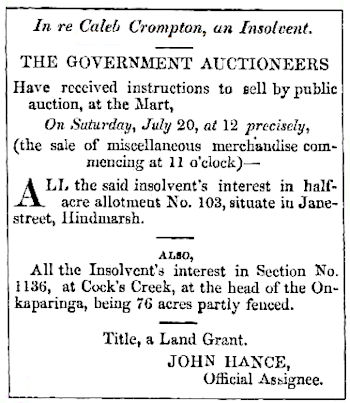

On Monday 04 February 1850 page 4 of the Adelaide Observer begins the first of many references to Caleb's insolvency.

|

| Caleb Crompton, formerly of Hindmarsh, and late of Cox 's Creek, general dealer. who declared himself insolvent on the 10th December last, and was afterwards taken in execution, and committed to prison at the suit of James Carns. He petitioned the Court for relief. A fiat was issued yesterday, and the Commissioner sat to, adjudicated the matter, and declared that the petitioner was insolvent before the 24th January, the date of his committal. |  |

Fiat: In old English practice, a short order or warrant of a judge or magistrate directing some act to be done; an authority issuing from some competent source for the doing of some legal act.

On Thursday 07 March 1850, the South Australian Register reported that:

Caleb presented a petition, when his creditors were to prove his debts and vote for the

appointment of assignees - a person to whom some right or interest is transferred, either for

his or her own enjoyment or in trust. That day Caleb surrendered to his bail for examination.

Mr Bakewell opposed him on behalf of James Frew Esq. Debts were set down at £100 (£11300 in 2018)

and his assets at £103 (£11639 in 2018) ‘but latter were

merely nominal, as there it but one good debt of £3 (£339 in 2018) and some land, which is

mortgaged. He was examined at considerable length respecting his horse-dealing transactions, and

his evidence was contradicted in many respects by that of James Frew, Esq , who was also examined

on oath. The insolvent was unable to prove that he had given due notice to his creditors; and the

hearing was adjourned until the 21st March, when he will be examined touching the land referred to

in his schedule.’

James Frew, Caleb’s accuser, lived at Fullerton, near Glen Osmond, to the south-east of Adelaide. On Christmas day 1849 at fire broke out in the stables on his farm. Uninsured damage was £400-£500 (£48,000-£60,000 in 2018). ‘The fire is supposed to have originated from a person smoking in the stable.’ Caleb’s revenge !!!!!

Saturday 09 March 1850 - A second fiat was issued at noon.

Friday 22 March 1850 South Australian Register page 3 –

COURT OF INSOLVENCY At the hearing ‘The insolvent [Caleb] was subjected to a long examination,

which showed that he had been entrusted by [people] in Van Diemen's Land with horses to sell on

their account in South Australia. He made no return for the horses he disposed of except £20

(£2,400 in 2018) and for that he admitted he received a consignment of apples. He sold, bartered,

and exchanged the horses for various kinds of property, and after trading some time purchases a

section of land containing thirty-six acres, ten acres of which he said (--stated) before he has

seen the land. He built a house on the ten acres he sold and finally became insolvent.’

The examination was adjourned till (sic) the 11th April.

Saturday 13 April 1850 Adelaide Times –

|

| In the final examination Caleb was opposed again by Mr Bakewell on the part of Mr Frew. The issue appears to be the sale of the horse Lincoln Hero, which Caleb had obtained from Mr Frew without payment. Caleb had sold the horse to pay another debt of longstanding to a person named Cummins whom he had seen at the Balhannah Show. Mr Bakewell argued this fraudulent transaction had taken place on 9 December 1849, the eve of Caleb’s insolvency. He prayed for a further adjournment. However, the Commissioner ruled as Caleb had been frequently remanded, and there was no other proof or opposition, he considered Caleb entitled to the relief prayed for. This I interpret as Caleb being found not guilty. |  |

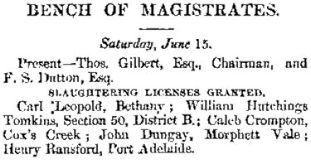

Licence to slaughter

|

| After his insolvency in Adelaide and whilst living at Cox’s Creek, the South Australian Register of Tuesday 11 June 1850& records Caleb living in Cox's Creek and applying for, but did not attend the magistrates, a licence to slaughter. Perhaps this was related to the distance he had to travel. The Adelaide Times of Monday 17 June 1850 shows a licence to slaughter was granted by Messrs Thos. Gilbert, Chairman; and F. S. Dutton when Caleb attended. |  |

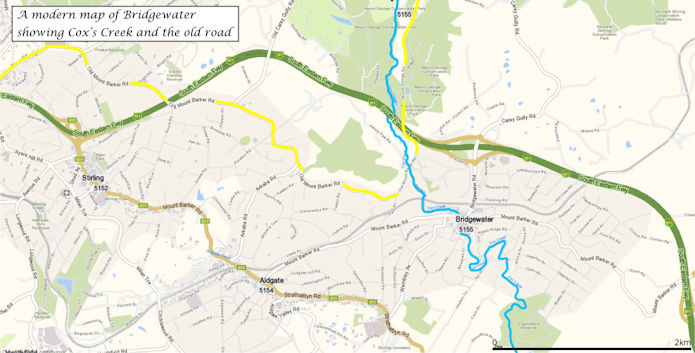

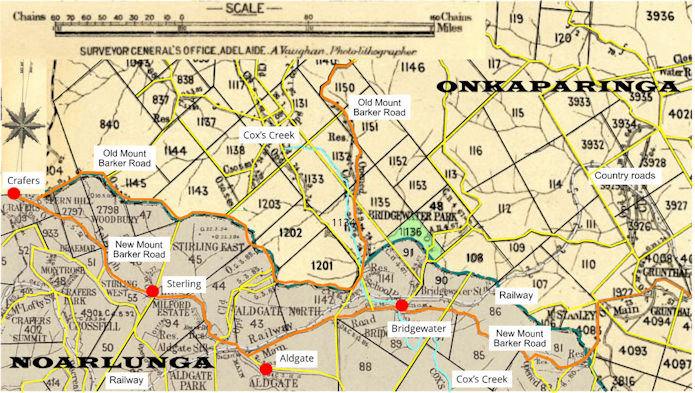

Locating Caleb’s home at Cox's Creek - Original named Cock’s Creek and later to the present day both Cox's Creek and Cox Creek. Cox’s Creek is used throughout.

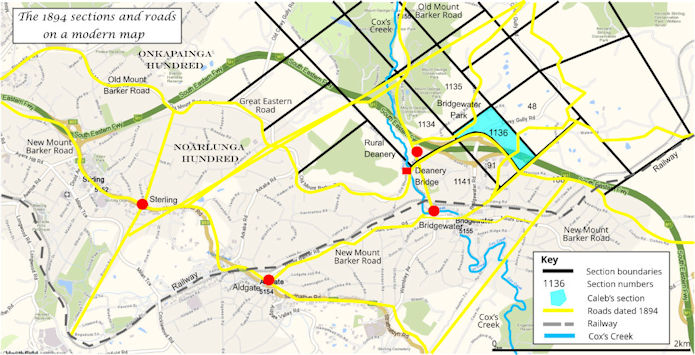

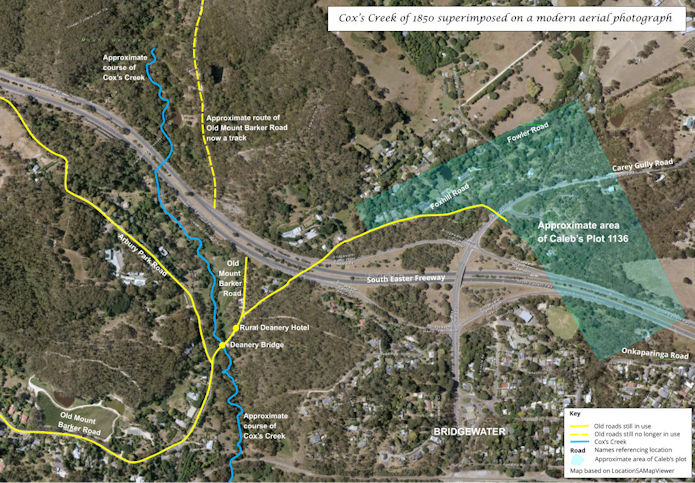

According to Reg Butler, in his work on Arbury Park and the Cox Creek Settlement, in 1849 Caleb Crompton had lived at Hindmarsh before setting up as a storekeeper along the Great Eastern Road 7 [Old Mount Barker Road] at Cox’s Creek. According to the insolvency papers, he took Section 1136 in the Hundred of Noarlunga (sic) 8, when it came up for public sale on 05 October 1849, following the Government survey. Something went wrong! By 2 February 1850, Caleb had become a bankrupt. Caleb left the colony soon afterwards, never to return.

The series of maps below attempt to locate this section from contemporary and modern maps. The key features are Cox's Creek, the Old Mount Barker Road and the modern South Eastern Freeway in the vicinity of Bridgewater SA.

|

| Above: A modern map showing Cox's Creek in blue and Old Mount Barker Road in yellow Click on the map to open an A4 pdf in a new window |

The numbered settlement section of Cox's Creek cross the boundary of the Onkaparinga and Noarlunga Hundreds; the boundary being, in part, the Old Mount Barker Road/Great Eastern Road. The 1894 roads were more numerous than on the modern map. However, even in 1894, some of these tracks had been straightened or closed.

Since the 1894 map, the settlements have spread increasing in size, shifting their centre from what may have been a cross road. The more southerly New Mount Barker Road and the railway had been constructed.

|

| Above: Settlement sections around Bridgewater in 1894 based

on the combined maps of the Onkaparinga and Noarlunga Hundreds. The sections available

for settlement are numbered. Caleb's section is coloured green Click on the map to open an A4 pdf in a new window Source: State Library of South Australia (Accessed: 26 June 2019) |

|

| Above: Bridgewater settlement sections on modern overlay Click on the map to open an A4 pdf in a new window |

The map above overlays the 1894 sections and tracks on the modern map. This best fit, rather than a precise overlay, is orientated on the railway and the Old Mount Barker Road with the time related discrepancies of scale and surveying.

That said, it is possible to make a general location of Caleb's section based on the location of section 1136 and the written description of the section related to Deanery Bridge and the Rural Deanery Hotel.

When Caleb's inverted boot shaped section is overlaid on a modern aerial photograph it nestles in the Bridgwater slip roads (ramps) of the South Eastern Freeway. The southern boundary of the inverted boot toe is marked by Foxhill Road before it branched into an area of detached housing. In late 2018 through to early 2019, three bungalows in the Foxhill Road were sold with prices ranging from A$563K to A$1.26M, all on Caleb's section.

|

| Above: A modern aerial view of Cox's Creek with Caleb's

section overlaid Click on the map to open a pdf in a new window Source: LocationSAMapViewer (Accessed: 20 July 2019) From an idea by Heather Schoffelen - with thanks |

In 1850, besides their plant nursery on the 90-acre Section 1134, in the Hundred of Onkaparinga, George Davies and William Bunce operated a general store somewhere just by the Deanery Hotel to take the place of Caleb Crompton’s business further up Old Mount Barker Road, which had gone bankrupt in February of that same year.

A history of Section 1136

Section 1136 Hundred of Onkaparinga

5/10/1849 Land grant to Caleb Crompton of Bowden farmer. 36 acres for £36.

Subdivision 1. Application 19511.

20/8/1849 10 acres sold to James John Rudd woodsplitter Cox Creek. He used to rent this land out.

20/7/1850 Rudd made an agreement to sell the land back to C Crompton, but he never paid any money or made a claim to the property.

11/11/1882 Application to bring the land under the RPA. Land worth £200. Title to be made out to JJ Rudd

Subdivision 2. Application 118580.

C Crompton retained this land.

5/2/1850 C Crompton, now of Cox Creek, general dealer, went bankrupt. He had mortgaged his estate to John Richardson for £26. He had a cow, calf and foal, together with household furniture, all worth £10. John Hance was the official assignee. Crompton also had half an acre at Hindmarsh.

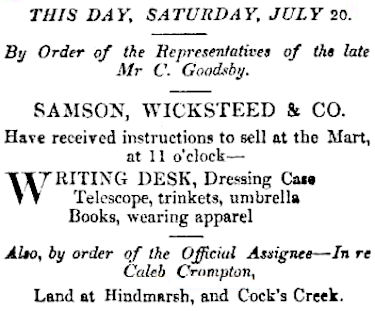

20/7/1850 Sampson, Wicksteed & Co held a public auction. John Richardson bought the land for £21. Crompton left SA shortly after the sale and never returned.

23/3/1853 James Rudd agreed to buy the land for £35. He leased the land to various people, including his four sons and Robert Paine gardener Bridgewater. A Wilhelm August Schuster gardener Bridgewater was a witness to a lease made in 1882.

12/5/1881 JJ Rudd brought the land under the RPA. Worth £400.

17/5/1882 Rudd made an agreement with Maurice Coleman Davies to lease the land for £25 per annum, with right to purchase for £600.

Source: Bridgewater - Early Land Sections Butler, Reg, Extracted from Hahndorf Historian (Accessed: 20 July 2019) With thanks to Heather Schoffelen

In summary:

Birth of his son Charles Walter

On 07 April 1850 Caleb's son Charles Walter was born at Cox’s Creek.

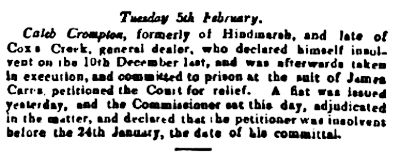

Auction of Caleb’s assets

Around 5 July 1850, The Adelaide Times makes frequent reference to the notification of the sale, by public auction, of the interests of Caleb Crompton by Samson, Wicksteed & Co on 20 July 1850, commencing at eleven o’clock. His assets were recorded as half-acre allotment, No. 103 situate in Jane-street, Hindmarsh; also Section No 1136, Cock's Creek, at the head of the Onkaparinga [river] and partly fenced. Unspecified miscellaneous merchandise/sundry other articles were also to be included.

|

| The Times of 20 July 1850 went into more detail listing items of some opulence

including a ‘Writing desk, Telescope, umbrella, books.’ This testifies to Caleb’s

literacy. It should be noted that Mr C. Goodsby called this debt: a new creditor and

perhaps one at Cox’s Creek.

John Hance, the Government assignee, shook a sad head over Crompton’s assets - a cow, calf and foal, together with household furniture, altogether worth £10. On a grey winter day in July 1850, Sampson, Wicksteed & Co auctioned Crompton’s Cox’s Creek land for £26. Source: Bridgewater (Cox Creek Valley) Settlement (Accessed: 18 June 2019) |

|

There are no South Australian Trove references after 18 June 1850 to 31 December 1850.

Why did Caleb become insolvent again and move on - a hypothesis

In 1849, Cox’s Creek fostered two burgeoning industries: iron smelting and a saw mill. GM Stephen's Forest Iron & Sawing Company 3 was based on sections 1118, 1117, 1130, 1131 and 1138, which were close to Caleb's property where he is described as a 'general dealer'. The saw mill employed 60 to 70 men in a village of about twenty slab huts and workshops in section 1117, plus visiting bullock team driver. There is little evidence of iron workings and the saw mill was offered at action on 17 July 1850, at the same time as Caleb's insolvency auction. The sawmill eventually failed around 1860.

This leaves the intriguing question. Had Caleb invested in the sawmill or had his business suffered from the prospect of losing customers who worked at the sawmill?

Conclusion

In 1866, RP Whitworth wrote his descriptive words thirteen years after Caleb and family had moved from Cox’s Creek. Had he stayed Caleb may have established the profitable farm described in his 1845 letter and Fanny may have had a more secure life. However, when Frances Crompton died in Miners Res in 1901, her death certificate declared she has been resident in Victoria for 48 years. This would suggest she and Caleb left South Australia in 1853. This may have been a hearsay date. If it is an accurate date, where had the family been between 1850 and 1853? The Bridgewater (Cox Creek) Settlement records that Caleb 'left the colony soon after [the auction] never to return'.

Postscript

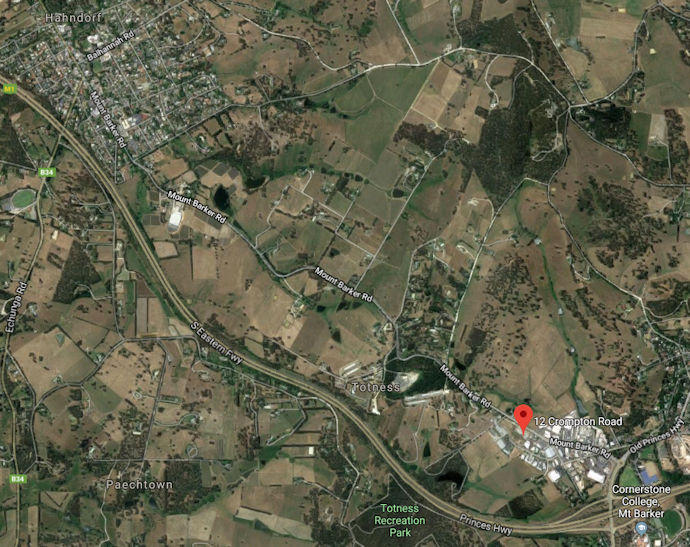

In July 2019 a light industry site was offered for sale at 12-16 Crompton Road, Totness at a cost of A$1.95M + GST. This is described as a 1.929 acres of 'Rare development site of development land in booming area' located in Mount Barker’s fastest growing and most sought after commercial area, near to Bunnings and the South Eastern Freeway. Crompton Road is 7km from Bridgewater, with Hahndorf halfway between, and is located off the Mount Barker Road.

|

| Above: Map locating Crompton Road, Totnes |

|

| Above: Map locating Crompton Road, Totnes with the for sale plot marked. From an idea by Heather Schoffelen |

Hoverbox Photo Gallery - Tioga wagon road

This feature does not function correctly on phones and tablets.

In September 2020, whilst in the Yosemite National Park, I walked part of the Tioga wagon road (The Great Sierra Wagon Road) now replaced by Highway 120. I was immediately struck by an imagined similarity with the Great Eastern Road (Old Mount Barker Road) in the days when bullock train made their way from Adelaide to the Bridgewater area.

| 1 Tioga wagon road 2020 | 2 Tioga wagon road c.1890 |

| 1 | 2 |

|---|

| More information 1 |

A short history of Cox's Creek around Caleb's time

Introduction

This paper is intended to give a flavour of the Cox’s Creek experienced by Caleb when he lived there. Known as Cock’s Creek and Cox Creek, the settlement is referred to as Cox’s Creek throughout, except in quotes.

Cox Creek, one of the most sequestered and loveliest of the valleys of SA.

First settlement

RP Whitworth wrote in1866: The district is an agricultural one, and is to a great extent taken up by market gardeners, the soil in the gullies being peculiarly adapted to the growth of vegetables and fruit [for the Adelaide market].

Early on Christmas Day 1837, Robert Cock and a small party of European colonists set out from Adelaide, to blaze a trail over the Adelaide Hills to the Murray River. Declining an offer of Christmas dinner with some timber splitters near the vicinity of present-day Crafers, the four men made off further into the dense bush, ‘steering by compass, as there were no more stations of white men’.

A few more kilometres of travel completed, the group reached an annoying obstacle. William Finlayson recorded the incident years later:

We had not gone many miles when our horse got bogged in crossing what has ever since been named Cock’s Creek, but our united strength could not pull him out, and we were obliged to return to Crafers for help, when Mr WIlson and his stepsons willingly returned with us, and then by great exertions and main force we got him out and camped for the night.

Cox’s Creek rises in the Black Swamp, on the southern edges of the New Tiers, the earliest popular name for the Adelaide Hills and now called Mount Lofty Range, between Summertown and Uraidla. Quickly dropping in altitude tributary streams join before reaching the Creek near Bridgewater and before its ten kilometre journey to become a tributary of the Onkaparinga River.

Robert Cock eventually crossed the stream that would, in time, bear his name. However, it is likely that isolated bands of timbersplitters sighted Cox’s Creek before Cock himself did. With year-round running water seeping into deep pockets of sheltered, fertile soil providing ideal conditions for massive stringybarks and other trees to flourish in profusion, the lure proved irresistible.

Historically, Cox’s Creek soon assumed a significant role in European settlement of the Adelaide Hills. Due to the insatiable demand for timber to establish Adelaide, the Port and surrounding farms and villages on the Adelaide Plains, timber getters soon spread along the length of Cox’s Creek and its many tributaries. A mixture of runaway sailors, escaped New South Wales ticket-of-leave convicts, wanted criminals, cattle duffers and honest labourers built isolated bark huts beside permanent springs. Plains dwellers nicknamed these mountain-bound inhabitants Tiersmen, because they came from the Tiers Hills.

Armed with adzes and axes, the gangs went out with sledges drawn by bullocks, which hauled newly-felled logs up from treacherous gully depths and down from perilous mountain heights. Using saw pits, the timber getters reduced butts to straight lengths for vital construction projects. Splitters working near the source of Cox’s Creek tended to send timber for sale down Greenhill Road to Adelaide; those men quartered around what is now Bridgewater used the Mount Barker Road, now the Old Mount Barker Road - both routes then merely bullock tracks through dense bush land.

In its early days the intense isolation of Cox’s Creek was an area both for characters evading the law, or honest souls valuing solitude. Few casual day trippers wandered into the region. People could easily become lost in the tangled scrub with frequent winter fogs increasing the danger of falling unawares into one of the many unmarked sawpits littering the countryside.

A general description of the area

Under the title A Naturalist's Ramble on page 3 of the South Australian Register of Saturday 15 January 1842, a walk from Adelaide to Mount Barker described the area as having:

… many delightful scenes of hill and dale, of evergreen lands and flower-covered plains, touching a little on the accommodations met with on the way, and on our variegated scenery […] Our first ramble will be from Adelaide up the mountains, to the hotel (yes, a hotel on the mountains, and superior to many in the town) of our old friend Crafer in the Tiers, and lying in the sight of Mount Lofty as we face the range of the hills. We proceed by the Mount Barker road through a lovely and diversified country. This road, from its many singular and romantic features, and leading as it does over the tops of mountains, has often been likened to the pass over the Simplon from Switzerland to Italy […] the mountains, which rise before us in gently rounded slopes of every form and size, spread out like a verdant carpet, with grassy knolls here and there, and thickly studded with the straggling gum tree, which still prevails, with its airy foliage and curiously twisted branches, sometimes laden with hanging bark. Wild flowers of every hue, often combined with the most delicate smell, delight the eye and the senses on every side; they form one of the peculiar features of this country, [...]

[...] Within half a mile of our destined resting-place [at Crafer’s Hotel], the wood-lands begin to bear decided marks that the hand of man has been engaged amongst them, for the sawyers have here commenced felling those trees most serviceable at the beginning of the colony, being then used for building, and still for fencing, &c. This clearing gradually increases as we near the hotel, always of course the principal seat of attraction; it is calculated that the wood collected, in the yard of this building alone, will serve all the wants of the inmates for fuel for the next ten years, and there is no doubt that what at present is cut down would, if necessary, serve the town of Adelaide for fifty years to come, and additional timber being often wanted for other purposes, the place of all would soon be supplied by the young trees that would in the meantime spring up.

The tourist or naturalist (for I speak only of those who come for pleasure, not business) had better rest here the first night, and start by sunrise the following morning, to observe with renewed delight the various beauties still in store for him. As soon as the sun has thrown his gladdening light o'er the sky, we set forth, after a short breakfast, to the "Deanery", four miles further on the Mount Barker road. Again, a change comes o'er the spirit of the scenery, and novelties once more attract us; the road now leads through woods with foliage more closely set, but without bearing the least dark or sombre appearance. Here truly nature luxuriates unrestrained, for though the soil is stony, and bad for agriculture, which no one would think of attempting on these heights, yet it is of such a description that everything flourishes with redoubled vigor (sic). The innumerable flowers, plants, and underwood, of a size and growth several times larger than we have hitherto seen them, shoot up intertwined with each other in all their native wildness, giving to the mind the idea of an Indian jungle. The grass tree, as it is usually called, with its long subulate leaves, springing from the ground in many rays diverging from one point, is here very common, frequently bearing in its centre a bullrush eight or ten feet in length. Flowers, generally of a purple hue, are seen training up the stems of many of the trees, surrounded by others, combining every variety of colour that Flora's kingdom can present. A cloudless sky is above our heads, but the intense rays of the sun which now begin to shoot

obliquely through the trees, are agreeably leavened by the overhanging foliage. Insects without number, and of various kinds, wing their way on every side. Wasps and ichneuinom flies, some of a golden hue, hover round the native honeysuckle, which, with many other sweet smelling plants, sends its delicate perfume on the air. At one turn of the road the whole atmosphere is scented with the exquisite smell of wild honey, proceeding from a waving sea of small white flowers rustling with the gentle breeze, among which thousands of bees are revelling in undisturbed enjoyment.

The Cox’s Creek Caleb may have witnessed

By 1840, very small numbers of permanent settlers (sometimes timbersplitters who had married and decided to settle down) had arrived beside Cox’s Creek, now an attractive area for family settlement. At the headwaters, market gardeners tilled the loam around the springs to plant apples, cherries, pears and plums, under which other exotics such as rhubarb, gooseberries and strawberries thrived in the damp. These small gardens also grew potatoes, peas, and cauliflowers, all of which commanded top prices on the Adelaide plains, where the warmer climate did not favour them to the same degree. Some landholders also raised seedlings for home vegetable plots.

These first cultivators endured long outdoor hours in often inclement weather, of bitter cold and blinding rain, to earn a living working the land. On other days produce was taken to the Adelaide market. Pockets of garden cultivation also began to appear at the headwaters of the various Cox’s Creek tributaries, where timber cutters had made clearings. Haphazard surveys meant that some sections were established on purchased soil; other settlers decided merely to squat on Crown land.

Where the flow of Cox’s Creek temporarily steadied its downward rush, the future site of Bridgewater appeared. Close to where Robert Cock and his companions had become stuck on Christmas Day 1837, the bullock tracks descended the ridge from Crafers in order to ford Cox’s Creek on their way to the Special Surveys 1. Months later, busy traffic bumped and splashed over Cox’s Creek, at the future Bridgewater crossing, to service farms on the Surveys on their main route to and from the early Adelaide Hills townships to Adelaide.

Hoverbox Photo Gallery - Bullocky

This feature does not function correctly on phones and tablets

|

1. Bullock teams on what may have been Old Mount Barker Road 2. Logging bullock teams, on what could have been the Adelaide Hills |

3. A bullock team in town hauling wool bales in town 4. The Bullocky, who may have called at Caleb's store |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|

The Great Eastern Road also known as Old Mount Barker Road began as a bullock ‘road’, which passed Caleb’s section and ‘store’ used for his general dealing. The Old Mount Barker Road would have witnessed the bullock trains and the Bullocky may have frequented Caleb’s establishment.

The whole clumsy arrangement lurched, tilted, creaked and groaned painfully on its axels. Timber and minerals one-way to Adelaide but more importantly domestic good for the stores and homesteads on the inward journey – sugar, tea, currents to Bridgewater and beyond. Distances covered were often considerable. Bean mentions journeys of 240 miles in a New South Wales where one man inhabited one hundred square miles and with one tank of water for teams of 18 or 20 or 26 bullocks yoked to one wagon. Slower than horse teams, the reliable bullock will go back the next day and pull the same load.

The bullock-driver, known as a ‘Bullocky’, was the source of most transportation as they opened the Australian hinterland on well-worn hauling tracks. Bean describes the Bullocky as a considerable man, a steady and deliberate philosopher of considerable opinion. In practically every case a gregarious man too generous to leave a ‘mate’ in bogged down in a creek. He treated his fellow man as one of his team. Most Bullockies are fair to their team, using the whip for the times when rutted wheels are stuck. When convinced the load is too heavy, the team was rested or the load lightened. At £7 (1910) each, they are his living. A ‘boss bullocky’, owning one or more than one teams, ‘superintends a considerable business’. In 1910, freight cost £4 per ton per 100 miles. He hope that the contract would be multiple journeys, knowing where the water and grass we to be found.

In camping alone over night after night by the side of the road, the Bullocky had travelled further than most Australians had. In doing so, he acquired a collection of interesting short stories and noticed every single thing, accumulated from his many bush journeys.

Bean, CEW, On the Wool Track, Alston Rivers Ltd, London, 1910 reprint pp.243-255

| More information 2 |

The Rural Deanery 2

A Naturalist's Ramble continues:

Such are the various natural beauties that everywhere we meet till we come in sight of the "Rural Deanery.” This is a small public house lately built, and kept by Benjamin Deane and spouse, a good-natured and worthy couple. It is placed upon the opposite bank of Cock's Creek, to which we descend by a rather steep hill. The water of this clear stream is said to be worth coming from Adelaide alone to taste. At the "Deanery", our appetites being sharpened by the walk, a cup of coffee will be found very refreshing in the small though neat parlour, where this agreeable beverage, with plenty of eggs, milk, butter, and home-made bread, will be served (perhaps) by the beautiful daughter of our host.

On 1 April 1841, Benjamin Dean, a former Cheshire farmer, successfully applied for a licence to operate a hotel - The Rural Deanery - on the eastern bank of Cox’s Creek above the ford, squatting openly on Crown land on what is now Arbury Park. Despite the illegal squatting anyone in the Adelaide Hills wilds appreciated the homely comforts of the Deanery - the first hostelry since leaving David Crafer’s hotel at the top of the ranges near Mt Lofty. In the small though neat parlour, Mrs Dean and her daughters, Anne and Elizabeth, revived weary travellers and served coffee, with plenty of eggs, milk, butter, and home-made bread.

|

| Above: The Rural Deanery EC Frome’s watercolour 3 Sketchbooks of Edward Charles Frome (as filmed by the AJCP) [microform] : [M987], 1835-1853. Sketches Album No. 2 of the Fleurieu Peninsula, River Murray, Adelaide Hills and Barossa Ranges Trove (Accessed: 16 June 2019) |

| Hoverbox Photo Gallery - Rural Deanery Hotel This feature does not function correctly on phones and tablets |

|---|

| 1. Deanery Bridge c.1900 | 2. Rural Deanery Hotel plaque | 3. Rural Deanery Hotel plinth |

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|

It had been originally established to cater for the passing bullock teamsters who battled their way along the Old Mount Barker Road at the refreshing waters of Cock’s Creek, but it soon became the focus of a mixed bag of the toughest bullock drivers and most depraved of early colonists and woodcutters on the rum.

Until about 1855 Cox's Creek consisted of a cluster of colonial cottages, a Post Office and a tiny school conducted by a Mrs Bruce, the wife of a local orchardist clustered about the Rural Deanery. Now, the original village of Cox’s Creek is nowhere to be seen, but a plaque beside the old bullock track records the first pub in these parts.

In 1853 the Old Mount Barker main road through the hills was re-routed 4. When the new coach road through Stirling and Aldgate (the present Mount Barker Road) was completed, it ran a little southwards of the Cox’s Creek settlement and the through what is now Bridgewater.

Dean's successor, called Addison, moved his hotel business there. Most of the village followed, and within five years the hotel on the new site became "The Bridgewater Inn" 5, believed to have been so named after Addison's home town in Somerset. In 1859, John Dunn set about building the Bridgewater Mill 6, the mill with the wheel next door. He had the land around the Inn laid out as a township, taking its name in turn from the Inn. That was the end of the old village of Cox's Creek. The new Mill needed a new dam that spread right across the gully, built above the village. It was badly built and in its first year of filling, the dam wall broke and washed what was left of Cox’s Creek away.

|

| Above: Bridgewater Hotel unknown date |

The cellar of the Rural Deanery were still there in the 1960s, about 20 metres uphill from the bridge, and overgrown with blackberries.

| Hoverbox Photo Gallery - Bridgewater Mill This feature does not function correctly on phones and tablets |

|---|

| 1. Bridgewater Mill c.1850 | 2. Bridgewater Mill c.1869 | 3. Bridgewater Mill c.1869 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|

End notes

| More information 3 |

| More information 3 cont |

|

The sale of the sawmill, offered by auction on 17 July 1850 at a time similar to the demise of Caleb’s general dealer business, claimed the buildings and machinery cost in excess of £6000 to erect and had been worked for only "about four months". This is likely to have been from November 1849 to February/March 1850 when the sawmill was fully operational. It was reported eleven persons purchased the properties. In evidence to the October 1849 libel case, a North Adelaide blacksmith named John Chambers who respectively in 1847 and 1848 sold sections 1118 and 1117 to GM Stephen, claimed he had obtained some iron ore from Cox's Creek a mile below section 1118. From this he cast two chisels after smelting it into high grade steel without the need to first produce cast iron and then remove the impurities. There is no documented evidence any iron ore whatsoever was ever mined or smelted on either of these two sections before or after Chambers sold them to GM Stephen. The slab huts were removed circa 1860 when the enterprise failed. The steam engine’s tall chimney for the boiler stood as a landmark for 60 years before it collapsed across the road in 1909. By 1872 the Adelaide press reported not a vestige of the sawmill was to be seen save the chimney-stack and part of the old boiler. Extracted from a longer article that can be found at An Early Adelaide Hills Sawmill Compiled by John Raymond, Brisbane, QLD, Australia - April 2013 (Accessed: 29 July 2019) Researched by Heather Schoffelen. |

Bibliography

|

|

|||||||

| This page was created by Richard Crompton and maintained by Chris Glass |

Version A8 Updated 07 June 2023 |

|||||||